‘Crossing a line:’ Emory University cuts DEI and fires faculty over Charlie Kirk post

At Emory’s first senate meeting of new school year, interim president Leah Ward Sears gave non-answers about cutting DEI and firing faculty for Facebook posts.

I got an email Sept. 8 from philosophy professor and new university senate president Noelle McAfee with the subject “Press welcome to Emory senate and faculty council meetings.”

“These meetings [were] previously closed to the press,” she wrote. Now that she was president of the Senate, which represents the private university’s students, faculty, postdoctoral researchers and alumni, she had a goal: “…to make ignoring us impossible. So I am opening up meetings to all constituents and to the press to observe.”

She was referring to Emory’s administration in the first part of that phrase. Both the Senate and faculty council are empowered by the school’s bylaws to weigh in on university matters, she explained in her email, but the same bylaws “also allow the administration to completely ignore our recommendations.”

Things happening at Emory may affect the larger Atlanta area, not just because the university has one of the largest endowments in the nation, but because the school is the metro area’s second-largest employer.

I’ve known McAfee since she was arrested along with 27 others on Emory’s quad last April, during a protest against Israel’s assault on Gaza and the police training center southeast of Atlanta known as Cop City. Atlanta police and state troopers used Tasers and gas and brutally arrested protestors and passersby (like McAfee) alike.

We had kept in touch; she kept me posted during the months of work that followed from Emory’s response to the protest, revising the school’s “open expression policy.” Now she was letting me know about the university’s Senate meeting. Attendees would meet Judge Leah Ward Sears, Emory’s new interim president, who had announced Sept. 3 that Emory would be ending its Diversity, Equity and Inclusion programs (DEI).

The president is barely a month into the new job, but she’s hardly an unknown name in Georgia. Sears graduated Emory Law School in 1980 and went on to become the first Black woman to serve as a chief justice on a state supreme court after being appointed to the position on Georgia’s highest court in 2005. She served on Georgia’s Supreme Court for 17 years.

Shortly after arriving to the high-ceilinged, naturally-lit auditorium, it was clear McAfee—and as it turned out, other faculty members—wanted to ask the new president about the eventful beginnings of the new school year, which also included School of Medicine Dean Sandra L. Wong announcing Sept. 18 that the school had fired pediatrics professor Anna Kenney for posts on her personal Facebook account that “caused concern.” The posts were in response to the killing of Charlie Kirk—a man who once publicly questioned the “brain processing power” of Michelle Obama and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson and called the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination in public places, among other things, a “huge mistake.”

Kenney’s offending words apparently included “Good riddance.” Dean Wong did not name Kenney or reveal the Facebook posts, but Emory’s student newspaper was able to triangulate Facebook and Twitter posts to establish both details.

As I grabbed a seat in the last row, a man to my right introduced himself as a recently-hired investigator for Emory’s Department of Equity and Civil Rights Compliance. To my left was a physicist from a former Soviet country who participated in shaping the university’s new open expression policy, which a preliminary Senate investigation had concluded was violated by Kenney’s firing.

The auditorium filled past capacity and an overflow room opened up to accommodate the crowd. McAfee handed out a sheet of paper summarizing events since last April’s protest, including the recent DEI cancellation and faculty firing. Another sheet of paper contained a resolution the Senate had passed on April 29 titled “The Lines We Must Not Cross.”

For McAfee, Kenney’s firing crossed one of those lines. In her introductory remarks to the packed room, she noted that one of the lines agreed upon by the Senate was, “We will not abide by or assist in the removal of any person from the University on the grounds that their speech causes offense.”

“Will Emory enforce its own open expression policy?” McAfee asked the room.

As for the DEI decision, McAfee noted in her remarks that the school had already gone back and forth with the federal government in April and May. The exchange came in response to the Trump administration’s threat to cut off around $485 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) if the school didn’t come into compliance with its interpretation of non-discrimination statutes. Emory administration and faculty spent several weeks changing program and service names and descriptions; the intent was to stop offering any program or service to any one group so the school couldn’t be accused of discrimination.

So it was that Emory “revised all DEI” in May, McAfee told me. As an example, she said, a program aimed at developing women in leadership was now solely a leadership program.

Nonetheless, on Sept. 3, less than a week in office, Sears sent an email to the Emory community announcing that, “Guided by the Office of General Counsel and other appropriate campus officials, we will work promptly and carefully to discontinue current DEI offices and programs.”

Three days later, McAfee posted a story on her Substack titled “Is Emory Joining the Club of Capitulators?” referring to other schools that had taken similar steps, even as the Trump administration’s legal right to condition federal funding on such demands is contested in courts across the nation.

After reminding her readers of Sears’ legacy as the first Black female Chief Justice on a state supreme court, McAfee wrote, “This past Wednesday she cemented a new legacy: a president who, in only her second day in office, effectively capitulated to Donald J. Trump and his administration’s attempt to rewrite history and set the country back 50 years.”

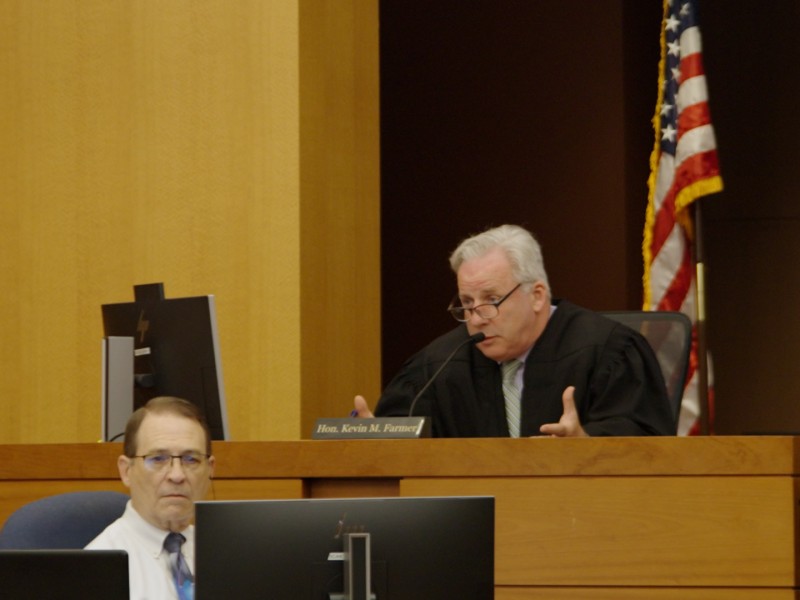

Into this maelstrom came Sears’ introduction to the Senate last Wednesday. She stepped to a podium shortly after 3 p.m. and spent ten minutes speaking about ideas such as “shared governance,” “collaboration” and “mutual respect.”

“I am committed to being as transparent as I possibly can,” she said.

The former chief justice said “many voices and perspectives” led to the decision to end DEI at Emory. “As you all know, the federal environment has shifted. I’m aware there are questions about the impact of the decision. I don’t have all the answers,” she said.

“Many people in the legal realm felt we needed to go further” than what had been done in the spring, she added, referring to the compliance work done in April and May. “What we did wasn’t enough to protect this university.”

George Shepherd, law professor and past president of the faculty senate, asked about Kenney’s firing. He had worked on the new open expression policy, which he called “the strongest of any private university in the nation.” That’s why, he said to Sears, “I was kind of stunned the medical school dean fired someone for words they posted on their private social media.”

Shepherd said the move was “in violation of the core principles of a university, and chills everybody. I hope you will be able to make the open expression policy enforced.”

Sears’ response: “I love the new open expression policy…[and] the firing of this individual was a personnel matter.”

Jehu J. Hanciles, world Christianity professor, stood up. “What definition of DEI is being followed? What programs and positions will be impacted?” he asked

“I can’t say that with certainty,” Sears replied. “It’s an unfolding thing.”

“Some of us are unsure if being acquiescent will be enough,” continued Hanciles, who was born in Sierra Leone—a country that has experienced dictatorship and military coups. “Are you aware of the erosion of trust this will create? The sense of loss?”

“Yes, I am,” Sears said. “When I was a law student here in 1977, this room would have looked very different. I have had anxiety about these issues all my life. I’m 70 years old. I didn’t just drop in. I can’t believe where we are.”

Questions to the interim president ended shortly after, and the meeting moved on to a presentation by campus police about how well they responded to the recent shooting at CDC, and how more officers, more surveillance cameras and other tools soon to arrive would make the campus safer.

Shepherd said afterward that the meeting was “very disappointing,” calling Sears’ reply to his question a “non-answer.”

“I was disappointed that the president, who herself was on the [Georgia] Supreme Court, is a lawyer and has recognized the importance of open expression and the First Amendment, didn’t speak about how the faculty member’s comments, although vile, should be protected.”

Reached a day after the meeting, McAfee said that being able to call any speech-related firing a personnel issue, and therefore not open to scrutiny, “completely hollows out the open expression policy. It’s a signal to the far right, while the administration is threatening to cut funding: ‘We bow down to you.’”

The Senate open expression committee would continue to investigate the firing to determine if it violated the open expression policy, she said. Meanwhile, the professor who was fired has received death threats, she added.

Emory spokesperson Laura Diamond declined to answer questions.

As for the school’s DEI, an Emory employee familiar with the compliance effort in the spring and who wanted to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation was left unclear about what had changed since then to bring on Sears’ announcement. “Nothing [she] said provided any insight or any meaningful context about why this needed to happen,” he said.

I also spoke to Emil’ Keme, an Indigenous K’iche’ Maya scholar and professor in Emory’s Native American and Indigenous studies program, whom I interviewed last year after he was arrested during the protest. Keme, who had escaped a violent civil war in his native country of Guatemala while still in his teens, told me last April that the police response to the protest made him feel “like I was in a war zone, with all the police and their weapons, the rubber bullets.”

He had followed the Senate meeting remotely, streaming it online.

Regarding the faculty firing and the notion that it was a personnel issue, Keme said, “I kind of anticipated that that would be her response. But I think it’s bullshit. It’s alarming. What can we say? What can we not say?”

Speaking about Kirk, he said, “This guy was a white supremacist. He doesn’t think Black women are intelligent. Why didn’t she say anything about this?”

Keme said he recently taught a class about Muscogee Creek people being driven from the southeast; students drew parallels between those 19th-century state terror policies and “what’s happening with immigrants today.”

“What am I supposed to say?” he said. “Just stick to the text? The students are not stupid. Some are people of color.”

“I was hoping to hear a more assertive message: ‘Continue doing what you’re doing. We’re going to protect you,’” he said about Sears’ remarks.

The exchanges between the new president and faculty at the meeting were “not surprising,” he said. “But at the same time, it makes me feel not safe.”

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn't cheap to make.