‘House of the Lord forever:’ What happened at Old Wheat St. and what lies ahead for Atlanta’s homeless camps?

In the wake of Cornelius Taylor’s death, Atlanta navigates the homelessness crisis with a new plan. But do its goals serve residents?

This story has been updated to correct the number of people Atlanta Rising plans to house to 400. A prior version of the article gave that number as 365.

Lolita Griffeth sat on her new bed, smoothing out her new, teal-colored summer dress.

She described the difference between sleeping in a bed since mid-July and sleeping in a tent on Old Wheat St., near Ebenezer Baptist Church and across the street from the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Park, for eight years.

“When you’re outside, you gotta worry about rats, or a man coming into your tent, or snakes, or whatever,” she said. “I used to have to get high just to fall asleep. Now I don’t have to do that.”

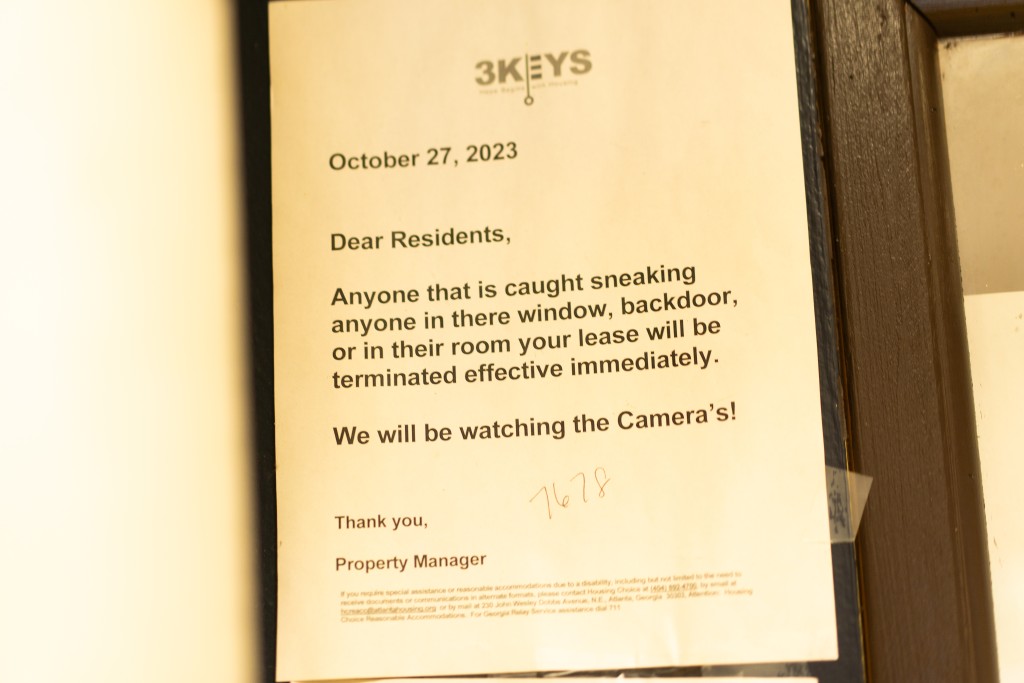

Griffeth was one of twenty-two people living in tents on Old Wheat St. who recently received a room and a key at Welcome House—apartments “for some of Atlanta’s most vulnerable residents,” according to 3Keys, which owns the property.

She was finally given housing after six months of activity surrounding the camp in historic Sweet Auburn, including the city council passing a resolution on homelessness; the City of Atlanta forming a Homelessness Task Force; the task force issuing 45-day and 90-day reports; and finally, the city of Atlanta announcing a July 10 sweep of the Old Wheat St. camp, followed by a few weeks of contentious negotiations and political theater surrounding the search for housing for nearly all the camp’s inhabitants.

All this activity arose because the city killed 46-year-old Cornelius Taylor, Griffeth’s fiancé, during a Jan. 16 sweep through the same Old Wheat St. camp. An unnamed city employee drove a front loader truck into a tent where Taylor was sleeping, days before the MLK holiday weekend.

As yet, there’s been little examination of these events—the resolution, the meetings, the reports, the theater—and their possible meaning for Atlanta’s nearly 3,000 unsheltered people moving forward. Taking a closer look seems particularly important in light of Mayor Andre Dickens’ vow to clear homeless camps in downtown Atlanta in the remaining months before eight games of the FIFA World Cup are played at Mercedes Benz stadium next June and July—not to mention the current administration’s war on the unhoused, as demonstrated by Vice President JD Vance’s recent rant in Peachtree City, when he said, “You should not have to cross the street in downtown Atlanta to avoid a crazy person yelling at your family. Those are your streets.”

Vance’s comment echoed one Mayor Dickens gave at an early summer press conference: “We want to make sure those unsheltered individuals don’t come anywhere downtown, and throughout the city of Atlanta, not just during the World Cup, but now.”

On some days, Griffeth still imagines she’ll see Taylor again, who she said “played too much”—as if his death was staged, a bad joke. “I keep waiting for him to pop out,” she told me.

Powerpoints and lofty language: The city takes on homelessness

On Jan. 23, a week after the Atlanta worker ran over Taylor, Atlanta City Councilmember Liliana Bakhtiari held up a poster during a council meeting with a photo of him smiling. In red letters, it said, “Justice for Cornelius Taylor.”

“There has to be a change in how we handle homelessness,” Bakhtiari solemnly said to fellow council members and the public, which included Taylor’s family. “It is not working. It has not been working. You don’t sweep encampments; you house them,” Bakhtiari continued. “Cornelius Taylor deserved to be housed. Housing is a human right.”

The council approved a resolution introduced by Bakhtiari on Feb. 3. Although its long title and most of its text center on declaring a moratorium on homeless camp sweeps until the city develops a method of doing so without killing anyone, the legislation also includes some lofty language.

It asserts the “need for accountability, [and] transparency” and declares that the city council is “resolved to take swift and decisive action to prevent further harm, rebuild trust with the community, and implement sustainable, equitable, and compassionate solutions to homelessness.”

It also specifically names Partners for Home, Atlanta’s “designated partner to coordinate homelessness services,” handing the nonprofit the job of creating a report in 45 days that explains how to avoid fatalities while sweeping camps.

The city then announced the formation of a task force with 36 public and private agencies and organizations, including staff from the mayor’s office and Fulton County, as well as Ebenezer Baptist Church and the nonprofits Intown Cares and Partners for Home. In the following months, the task force met at least twice as a whole: on April 8, with 29 members in attendance, and on May 6, with 15—less than half the announced membership. Four subcommittees of the task force also held meetings.

The city and task force wound up issuing the 45-day report—not Partners for Home. The report was twelve PowerPoint slides laying out a five-step process for sweeping homeless camps. It also includes four “key observations”—one being “insufficient resources throughout the ecosystem,” a bullet point leading to no specific action.

On June 10, the second and final report detailed 11 steps to “encampment decommissioning,” including “new protocols for shelter-resistant individuals.” The two-pager went on to recommend “identifying resources” and “opportunities” and “prioritizing future housing development.”

In the last paragraph, housing is mentioned once more. Anyone interested in the new approach to homelessness that the city developed after killing a man sleeping in a tent and holding months of meetings is assured, “These recommendations aim to…expand access to housing.”

The document has city employee Chatiqua Ellison’s name on the bottom, and lists her as the city’s “director of special projects.” So I asked her a series of questions about what specifically the city would do to create more affordable housing, by when and who would be held accountable for meeting these goals.

The questions were sent twice to Ellison. They were cc’d to LaChandra Burks, Atlanta’s chief operating officer (COO), and Michael Smith, a city spokesperson whom Burks named in a separate email after I queried her about the task force’s work. I also queried Bakhtiari, since the council member’s resolution and lofty language had helped set in motion the months of activity.

None of them answered. But unexpectedly, and bizarrely, Smith offered up a statement from Mayor Dickens in response to President Donald Trump’s recent executive order on homelessness.

Among other things, the president’s order promises to deny federal funding to any jurisdiction that employs Housing First, the method developed by psychologist Sam Tsemberis in the early 1990s that leads to housing chronically homeless people, like most of those at Old Wheat St. It is now followed in dozens of countries. Housing First has repeatedly resulted in high percentages of people remaining in housing, while centering the lives of those same people. It is also the method Partners for Home says it uses.

The statement from Dickens heaped praise on Atlanta for addressing homelessness and called the issue “a challenge no city can solve alone,” adding, “We need increased support from our federal, state, local and philanthropic partners.” But it said nothing about the order itself.

So I sought Dickens’ take on Trump’s new policies.

Again, no answer. And again, all these details will become increasingly important in the coming months, as the city makes sure “unsheltered individuals don’t come anywhere near downtown.”

In late May, a group called the Justice for Cornelius Taylor Coalition publicly resigned from the city’s task force due to what they said was the task force’s “unwillingness to address the systemic issues” underlying homelessness in Atlanta.

The group produced its own detailed, nearly $2 million plan centered on Housing First, the approach discredited by Trump.

The coalition gave the plan to the city, which ignored it, according to coalition member and American Friends Service Committee Atlanta Economic Justice Program Director Tim Franzen.

Housing First: What it is, and isn’t

Housing First’s basic premises include: housing is a human right; people on the street generally want their own housing, above other needs; a place to live should come with no conditions regarding sobriety, religion or anything else; and quality wrap-around services to help with mental health, addiction and other issues should be made available to people once they’re in housing. The method includes mandatory, usually weekly meetings with a case manager, a relationship predicated on centering the “client,” or formerly unhoused person.

On some days, Griffeth still imagines she’ll see Taylor again, who she said “played too much”—as if his death was staged, a bad joke. “I keep waiting for him to pop out.”

The method was developed working with chronically homeless people, which the federal government defines as being homeless for at least 12 months, or at least four times in the last three years. Atlanta’s chronically homeless population has grown more rapidly than any other subpopulation in the last eight years or so, going from an estimated 332 people in 2017 to 736 last year, an increase of 122%. Other subpopulation categories include families and youth.

One thing that has helped convince otherwise skeptical lawmakers to adopt Housing First is that chronically homeless people are more likely to be dealing with mental health problems and addictions, and wind up costing taxpayers a lot more when they’re on the street than if they’re in housing.

In its original and intended form, the housing offered by the model is what’s known as “scattered site,” meaning unsheltered people get to choose where they want to live in the wider community, most commonly with rental assistance through federal or state-funded vouchers.

Over time, many organizations have instead opted for “congregate” Housing First models, where formerly unhoused people live together in one building or buildings, and usually have access to some services on-site or nearby. This model makes it “easier to provide services,” Tsemberis, the creator of Housing First, told me. Missing from this approach is “the issue of dignity,” he said. “Is this the kind of place you would invite your grandchildren for dinner?”

This is the model at Welcome House. Partners for Home’s “Atlanta Rising,” a $212 million plan to “end unsheltered homelessness,” will mostly involve formerly homeless people living in the same housing, in separate apartments equipped with bathrooms and a kitchenette. It has a target of housing 400 people downtown. The plan relies on building and identifying hundreds of apartments and has a goal of “improved appearance and livability of the Downtown area in preparation for the FIFA 2026 World Cup and beyond.”

When municipalities such as Atlanta break up homeless camps, a public or nonprofit official is often quoted in the press afterward saying that a certain number of people didn’t accept the offer of going into shelters. Sometimes these people are called “service-resistant” or “shelter-resistant.” But Housing First does not consider shelters as a tool for helping chronically homeless people into housing. Most people living on the street, particularly the chronically homeless, try to avoid shelters. “Shelters are not housing,” said Brian Goldstone, author of “There Is No Place For Us: Working and Homeless in America,” a recently published book centered on homeless families in Atlanta. “The fact that many people would prefer to be on the street says more about the condition of shelters.”

For most chronically homeless people, “shelters are not a good option,” Tsemberis told me. “They don’t feel safe, there’s bullying, violence and curfews. With the pressure of all that, it seems better to stay on the street, where you have more control.” That’s why “service” or “shelter-resistant” are misleading and inaccurate as terms. “You’re blaming a person for inadequate services,” Tsemberis said.

Another vital part of Housing First is consistent outreach to people on the street, resulting in trusting relationships. According to Tsemberis, “Most chronically homeless people have been ignored, or worse, vilified,” and have a reserve of distrust. Cultivating trust is key to getting chronically homeless people to consider services or other support an organization or person may be offering.

After interviewing and spending time with people who lived in the Old Wheat St. camp and members of the coalition, I could see trusting relationships between the two groups. Some of the coalition members had been to the camp dozens of times.

The “math ain’t mathin’”: A fight over housing everyone at Old Wheat St.

Prior to the second planned sweep of Old Wheat St. on July 10, Atlanta officials and Partners for Home made a list of 14 residents who would be offered rooms at Welcome House once the camp was destroyed. The coalition insisted that more than twice that number lived on the street and wanted and deserved housing.

As a result, members of the coalition spoke with Old Wheat St. residents about ways to resolve the conflict and underscore how everyone in the camp deserved housing. Five residents who were not on the city’s list—including Griffeth, Cornelius Taylor’s fiancé—agreed to go to City Hall and address lawmakers directly during the July 7 City Council meeting.

But before the residents could speak to the Council, coalition members Tim Franzen and Nolan English, founder of Traveling Grace Ministries, got on a three-way call with City of Atlanta officials, including Burks, the city’s COO. Franzen paced outside the city council chambers while talking on his cell, even as the meeting unfolded nearby. English sat at a table with people from Old Wheat St., including Griffeth. At one point, English said, “The math ain’t mathin’”—meaning, more than 14 people needed housing.

Franzen told me that the residents and coalition members were prepared to occupy City Hall if their demand for housing for everyone wasn’t met.

Burks suggested they meet in the Mayor’s office, on the second floor. City staffers were surprised to see the residents, Franzen said—including Griffeth, who uses a wheelchair wherever she can after sustaining a stroke several years ago.

It was the first meeting between city officials, Partners for Home, the coalition and, most importantly, Old Wheat St. residents in all the months since Cornelius Taylor had been killed.

Griffeth’s recollection of the meeting was that the city and nonprofit staffers didn’t engage her and spent a lot of time defending their list. “They already knew what they were talking about, but didn’t come back and say, ‘Do you understand what we said?’” she said. “I felt like it was just for show,” she added.

But Franzen said the city agreed to expand the list to include those whom the coalition had identified. “We wanted to center the residents’ goal,” Franzen told me about his reason for agreeing to the meeting. “They wanted housing.” He left the meeting “skeptical but optimistic.”

That same afternoon, members of the coalition arranged for vans to take people from the camp for a visit to Welcome House, which has 204 apartments mostly inhabited by people who have lived on the streets.

There are boxes on the walls containing Narcan, the drug that reverses overdoses. Some of the hallways smell like urine. But the rooms have keys, air conditioning and refrigerators. Almost everyone in the camp came away from the visit seeing it as the best next step.

When the day of the sweep arrived, the coalition arranged for U-Haul trucks to move the Old Wheat St. residents’ belongings to Welcome House. Members of the coalition clapped when people from the camp stepped into a bus that would take them to their new homes.

Unfortunately, on arriving, Welcome House informed the group that new residents had to have IDs and completed background checks before they could receive an apartment. As a result, a total of 14 people were turned away. A city staffer offered the group spots at a shelter. They responded with talk of returning to the street. Franzen and others stepped up, taking them instead to a Microtel by Wyndham, where they wound up staying for weeks as other obstacles came up.

The struggle continues

By August, some of the remaining people from the coalition’s list went to Veterans’ Administration housing. A family had gotten into an apartment, paid for by the city. Two people found spots in a rooming house that would let them stay a month, paid for by the coalition. One went to a shelter at the Salvation Army. One went to another camp on the street.

Twenty-two people from Old Wheat St. moved into Welcome House. For nineteen of them, their rent is being paid for 12 months by Partners for Home, costing them $228,000 – a figure that includes a case manager, according to a contract shared with me. This and other information about Partners for Home was provided by Atlanta PR firm Jackson Spalding. The agency would not disclose the cost of its services.

Despite many of the Justice for Cornelius Taylor Coalition members not being case managers, social workers or professionals in related fields, they continue to meet weekly with the former Wheat St. residents, trying to provide as many of the wrap-around services the group needs as possible, since those services are not completely covered in what the city and Partners for Home have provided, Franzen said.

“I’m not a therapist, but I’m a human being,” Franzen said. “I know these people need to be heard and seen.”

Vassel said her organization “was in a difficult place” when it came to how things unfolded at Old Wheat St. The city and the coalition were doing most of the negotiating, despite Vassel’s organization paying for the rooms at Welcome House. “We didn’t have control over how it was done,” she told me.

CeCile’s room

Down the hall from Lolita, CeCile, who only wanted her first name used, was also settling into her new room at Welcome House. The 64-year-old has breast cancer and COPD, a progressive lung disease. She hopes Welcome House is the first step to getting her own apartment through Section 8, a federally funded voucher program that she applied to more than a year ago.

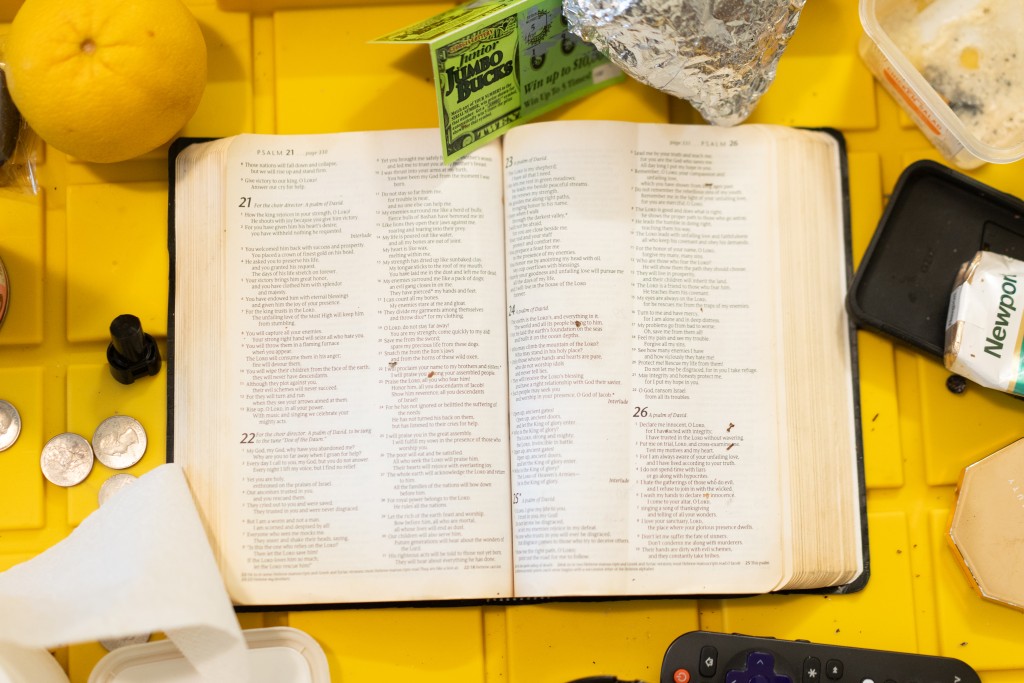

After only a few weeks, CeCile’s room showed signs of her personality. Her impressive shoe collection wrapped around two walls at the bottom of her closet. A Polaroid of her taken at Old Wheat St. rested on the windowsill. A bible sat on a coffee table, open to Psalm 23: “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord forever.”

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn't cheap to make.