Muslim life behind bars: From religious practice to retaliation

Imam Furqan Muhammad began volunteering his time in 1989 to support the spiritual and religious needs of incarcerated Muslims across jails and prisons in Georgia.

As a chaplain, Imam Muhammad wears many hats. He leads Friday congregational prayer known as Jummah, facilitates one-on-one pastoral counseling, distributes Islamic literature, and hosts open discussions where attendees pose questions, offer commentary, and engage in collective education.

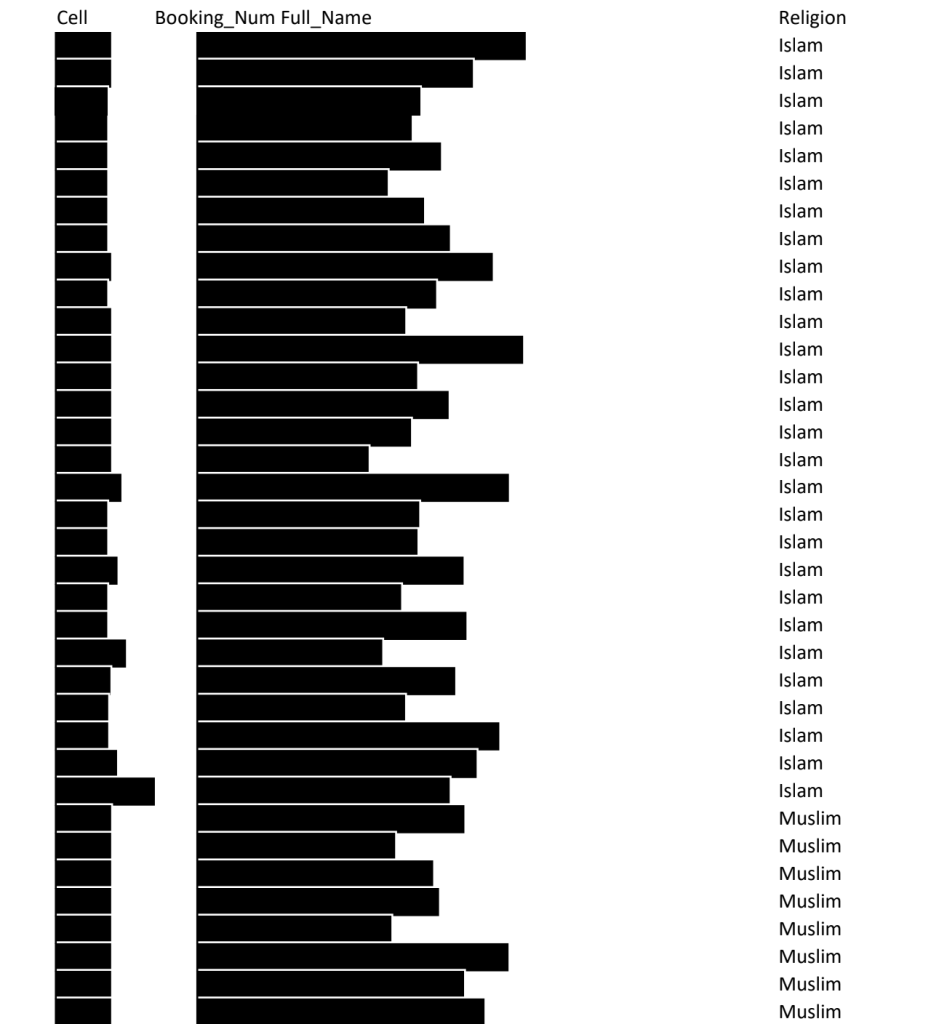

Fulton County Jail has the largest jail population in the state, including over 200 incarcerated Muslims. In a 2024 population profile, the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC), which operates state prisons, reported that over 2,000 incarcerated people self-identify as Muslim.

With over 35 years of service in county jails and state and federal prisons, Imam Muhammad has seen firsthand how changes in policy and practices impact incarcerated Muslims. He’s long represented their interests and has advocated for change in the carceral system.

“When we started there was no pork-free diet, there was no Jummah, there was no Eid prayer, there was no Eid feast,” he said.

GDC has since established guidelines for prison administration to adhere to, providing recommendations related to incarcerated Muslim’s observance of Islamic holy days, Ramadan, and more.

Eid al Adha, the most significant of the two Eid holidays, will be observed Friday, June 6. It’s a time when Muslims gather to pray and commemorate the Feast of Sacrifice.

“These things came because we fought. And now most of these institutions, they honor all of these things,” Imam Muhammad said.

Religious accommodation as a civil right

When it comes to Islamic faith practice, the ability to pray in a clean space five times a day at the appointed times, access to clean water for ablution—ritual washing of oneself in preparation for prayer, halal food options or other permissible healthy diet, and fasting during Ramadan are the building blocks to religious life.

During Ramadan, Muslims participate in a daily fast from food, drink, and specific behaviors between 12-16 hours a day. Incarcerated Muslims are completely dependent on jail and prison staff for timely distribution of healthy pre-dawn meals before the fast and nourishing evening meals to break the fast.

Religious accommodations are necessary for incarcerated Muslims to practice their faith. And federal law mandates it. While the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution establishes religious freedom, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 was passed to strengthen religious freedom, including to prohibit the government from second-guessing the reasonableness of a religious belief. Later, in 2000, the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act was passed to protect religious assemblies in land use and zoning matters. Ultimately, government agencies like jails and prisons are liable to protect the civil rights and religious freedoms of all incarcerated people.

Behind bars, being denied accommodations and the ability to practice an aspect of one’s faith can result in civil rights violations, as was the case at DeKalb County Jail. Last year, in February 2024, the DeKalb County Sheriff’s Office settled a $95,000 lawsuit after failing to meet the dietary and health needs of an incarcerated Muslim during Ramadan. Javeria Jamil, legal director for the Georgia chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), represented the plaintiff in the lawsuit.

Across jails and prisons, “food happens to be the number one issue for accommodation,” Jamil said. “GDC maintains that as long as they’re offering vegan food to Muslim incarcerees, then they have satisfied their requirement for accommodating people’s religious conditions.”

But it’s not that simple, according to Jamil. Not all vegan food is guaranteed to be halal. And the vegan options that are available in many facilities—similar to non-vegan options—typically don’t meet the health and nutrition needs of incarcerated people.

Over time, poor-quality food in scant quantities can make fasting during Ramadan unhealthy and unsustainable. This can impede a Muslim’s act of worship, which is unlawful.

Claims of retaliation, anti-Muslim bigotry raise stakes for educating jail and prison staff

Since 2021, CAIR’s Georgia chapter has received 63 complaints from incarcerated Muslims across the state’s jails and prisons. Issues range from not being allowed to pray Friday congregational prayer, not being allowed an Eid feast when other religious communities are allowed commemorations, and being denied religious literature. At least one person was denied a Qur’an copy that the jail didn’t approve of.

Some incarcerated Muslims say they’re targeted and retaliated against—either physically, verbally, or with restrictions to movement—when civil rights violations occur and a person reaches out for legal support. Jamil said her client’s unit was raided after he filed a complaint against DeKalb County Jail. He also reported being physically pushed down by officers.

As the country’s largest Muslim-led civil liberties group, CAIR publishes educational materials to help jail and prison administrators understand their duty to protect the rights of incarcerated Muslims. In past years, CAIR published a correctional guide on Islamic religious practices in addition to a press release on Ramadan accommodations, with the belief that knowledge of Islam can help mitigate some of the ignorance around Muslim’s religious obligations.

Imam Muhammad says a general lack of awareness about Islam, in addition to an atmosphere of anti-Muslim bigotry, has impacted the experiences of incarcerated Muslims. He’s led orientations in some facilities to teach staff about Islam and to respond to their questions. He strongly suggests that more facilities do the same.

“If the staff or leadership are ignorant, they’re gonna make bad decisions,” Muhammad said.

At the same time, regardless of the facility, Muhammad said it’s not uncommon for him to notice resistance from staff when it comes to enacting religious accommodations.

“We have deputies that don’t want to pull the inmate and bring him to Jummah prayer,” he said. “That’s their anti-Islamic mentality.”

Jamil said several of her clients believe they’re mischaracterized as a threat or members of a gang because of their perceived level of discipline and togetherness.

“Muslims are already the other. All their needs and all their rights become secondary,” she said. “Almost every person I speak to who’s in a jail or prison, it really does feel like people not being able to get their accommodation is a byproduct of general Islamophobia.”

Navigating pretrial detention, threats to bail funds

The time between a person’s arrest, pretrial detention, and first court appearance can last anywhere from a few days to several years. People in jail are sometimes granted bail, but if they’re unable to pay, they’re held in jail until trial.

“It’s possible [for someone] to be in jail three to four years and never been to court,” Imam Muhammad said.

A Harvard research series on mass incarceration and criminalization found that spending even one day in jail can have long-lasting, devastating effects—from loss of employment and housing to an accumulation of debt and diminished psychological well-being.

Muslims are among the many people detained in Fulton County Jail who haven’t been convicted of a crime and whom the law presumes are innocent. Fifty-nine percent of people in Georgia jails haven’t been convicted of a crime, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

“You go to court and they free you. Tied up years of a person’s life and they were innocent,” Muhammad said.

For detained Muslims who can’t afford to pay bail, community bail funds become a life-saving resource. Believers Bail Out, a grassroots effort to bail out Muslims from pretrial and immigration incarceration, raised over $2 million since 2018 to free hundreds of people who are presumed innocent under the law—some Georgia Muslims among them.

But since Georgia passed Senate Bill 63 last year, it has become more difficult for incarcerated community members to seek relief in this way. The new law puts limits on the number of cash bonds paid by individuals and charitable organizations to no more than three per year. This significantly reduces the amount of people who can be freed by nonprofit bail funds. As a result, incarcerated people remain in limbo while awaiting trial.

Since the impact of incarceration reaches far beyond the individual, for Imam Muhammad, serving Muslims behind bars continues to be critical work.

“The whole family is affected,” Muhammad said, “Everybody loses.”

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn't cheap to make.