Meet the ICE Chasers: the rapid response team keeping communities informed on ICE sightings

ICE Chasers in Georgia are organizing a grassroots response to fear, deportations, and attacks on migrants.

In the early morning hours before sunrise, two cars parked in front of a small store where day laborers ate breakfast and drank coffee before their days started. Volunteers with the Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights (GLAHR) stepped out of the cars to distribute information packets. The colorful, laminated papers included “know your rights” information and details about current legislation, like HB 1105, which authorizes local police to conduct immigration enforcement on behalf of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

A GLAHR organizer approached workers individually, speaking in Spanish. Many seemed unsure at first, but the majority welcomed the conversation, along with the invitation to contact GLAHR should they need support or if they see ICE activity.

GLAHR runs a program called “ICE Chasers” which started during the first Trump administration.

“We have tried to build up networks of communication with community members across the state of Georgia,” said Annette Aguilar, a GLAHR community organizer.

ICE Chasers are volunteers, including immigrant community members and allies, who maintain vigilance about ICE sightings in the areas they live in and report it to the wider ICE Chasers network. According to Aguilar, ICE Chasers form a “rapid response team” that keeps the community informed in real-time.

Matéo Penado is a volunteer with the ICE Chasers program and the child of immigrants from Mexico and El Salvador. They said that if someone thinks they see ICE, GLAHR has a hotline they can call, which can result in ICE Chasers across Georgia traveling to that location to verify. If ICE is conducting arrests at the site, they are encouraged to record video and take pictures.

But simply saying that someone has seen ICE agents doesn’t necessarily provide the information volunteers need, and in Penado’s words, can unintentionally become “fearmongering.” Details like what vehicle the agents were driving, what they were wearing and what someone observed them doing paint a fuller picture. This is why SALUTE reporting, an acronym for a strategy to describe potential ICE sightings, is so important. SALUTE stands for size, actions, location and direction, uniform and clothes, time and date, and equipment and weapons.

“A lot of the times when we see these things being posted online, they’re days old or it’s not even accurate information. It’s not been verified, as in nobody went out and checked,” Penado said. “One way of getting our power back is by making sure we are sharing accurate information.”

Fighting Fear

Trump’s policies so far have escalated anti-immigrant rhetoric and ICE enforcement in communities nationwide. Overcrowding in ICE detention centers has led to the transfer of asylum seekers and others detained by ICE to Atlanta’s federal prison.

Sofia, 26, shared her story as a Venezuelan asylum seeker who came to the Texas border pregnant to escape the Venezuelan army. Sofia arrived at the Hartsfield-Jackson Airport without a plan.

Sofia encountered members of Team Libertad, an Atlanta-based organization that accompanies asylum seekers at the airport through airport security. Volunteers with Team Libertad meet vans-full of immigrants, recently released from ICE detention and on parole. Most people are waiting on a flight but do not speak English, nor do they know how to navigate the airport.

Team Libertad connected Sofia to Casa Alterna, which provides a network of aid for asylum seekers and refugees, including housing. She was granted an open asylum case to apply for a U-visa, a program for victims of certain crimes such as domestic violence, sexual assault, trafficking, and other crimes. She now has a work permit. Sofia’s daughter was born in Atlanta in November 2023 as an American citizen. On Feb. 1, the Trump Administration removed Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelans in the U.S., threatening deportation for about 700,000 people.

Sofia works in the kitchen of a hotel in downtown Atlanta, where she says ICE agents have detained her co-workers. She has a lawyer with the Georgia Asylum and Immigration Network (GAIN) and knows her right to remain silent, but she also knows ICE could legally detain her at any time.

Her final court date in her asylum application process is not until June. If she is deported before being granted legal status, Sofia’s daughter would be left behind.

Penado said both of their parents and almost every single one of their aunts and uncles in Gainesville have worked in the local poultry factories.

“I drop my mom off at work every single night for her night shift, and she’s been telling me people aren’t driving themselves to work anymore,” Penado said. “Part of the reason why they do the ICE raids is to fearmonger and to scare these people into submission. Because if people can’t even participate in daily life, how are they going to be able to participate in any of these systems of power, much less work against them?”

Aguilar said, “Only the people save the people.” The ICE Chasers’ patrols provide a watchful eye in the darkness and voices in the quiet.

“Fear can immobilize you,” Aguilar said. “Fear can keep you shut in inside your home, scared to come out.” But allies can move despite that fear. She said white-identifying allies may have privileges like access to cars, speaking the English language and easier interactions with law enforcement. Allies can uplift GLAHR’s goal of community empowerment, Aguilar said.

She described the central feeling of ICE chasing: “I’m scared, and I’m scared to death, and I don’t know what’s gonna happen, but I’m fighting and I’m resisting and I’m community building.”

Know Your Rights

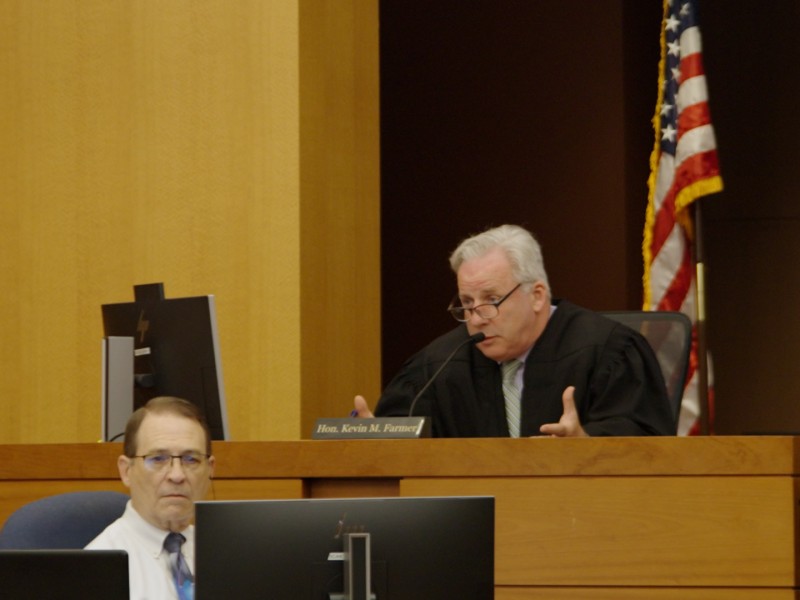

Joshua McCall is an immigration attorney in Georgia. When activists seek to thwart ICE activity or disrupt the system within the bounds of the law, McCall explains what’s legal and safe to do and what might get someone in trouble.

“I’ll tell you where the line is: It is a felony to do what they would call ‘aid and abet’ someone to either enter the country unlawfully or to remain in the country unlawfully,” McCall said.

ICE Chasers and others seeking to protect immigrant communities have First Amendment rights. McCall said posting on social media that there are ICE agents in a specific area is protected speech. “The news can’t get arrested for doing that and neither can individuals.”

If someone shares photos of ICE online with language that advises undocumented people to stay out of an area, that slight shift in the message can enter the grey area where charges of “aiding and abetting” are more of a possibility. According to McCall, it’s not common, but the current administration may be looking to make examples of people “aiding and abetting” in the future.

In February 2025, Elon Musk tweeted that the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) would cut “illegal payments” to Lutheran Social Services, a parent nonprofit of Team Libertad. Lead Coordinator and longtime Team Libertad volunteer Daphne has not been active in the airport for weeks, since no one is being released from detention on parole.

“Everything we did is within the law,” Daphne said. “People have a right to come to this country and ask for asylum.”

Team Libertad volunteers were targeted in January 2024 by Georgia Senator Colton Moore in a foisted attempt to expose “trafficking” activity and film immigrants in the airport. Since the White House instituted the Refugee Resettlement Ban on Jan. 20 which suspended funding for refugee resettlement agencies, there is uncertainty about the future of groups like Team Libertad, and refugee and immigrant aid work in general.

“What we’re trying to do is counteract the fear of this kind of terrorizing campaign,” said Anton Flores-Maisonet, co-founder of Casa Alterna. He organizes volunteer presence at immigration courts in Atlanta to offer hospitality and help people feel less alone.

Since Trump’s re-election, Casa Alterna opted out of a federal grant that would require the submission of names and ICE-assigned “A numbers” — or Alien Numbers — for every person the organization serves. This would create a budget deficit but morally, Flores-Maisonet said, it’s “the right thing to do.”

Sofia, who found housing with Casa Alterna for herself and her daughter, said in Spanish, “Ha sido más que un programa. Ha sido una familia.” Casa Alterna has been more than a program. It has been a family.

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn't cheap to make.