Opinion – Cop Cities are coming: Where will healthcare workers stand?

Most healthcare workers have historically stood on the sidelines as movements seeking social change unfolded. The opposition to Cop City in Atlanta has proven no different. We have seen our colleagues wholly uninformed or offering tepid support for the project. While discouraging, the past few years have illuminated the need for, and opportunity in, the political education of healthcare workers.

Despite their proximity to structurally driven preventable suffering and premature death, these experiences have not yet been molded into a sound political analysis, let alone a movement. While not a panacea, they remain a sorely missing piece in many coalitions looking to change narratives of safety and tip the scales of public policy.

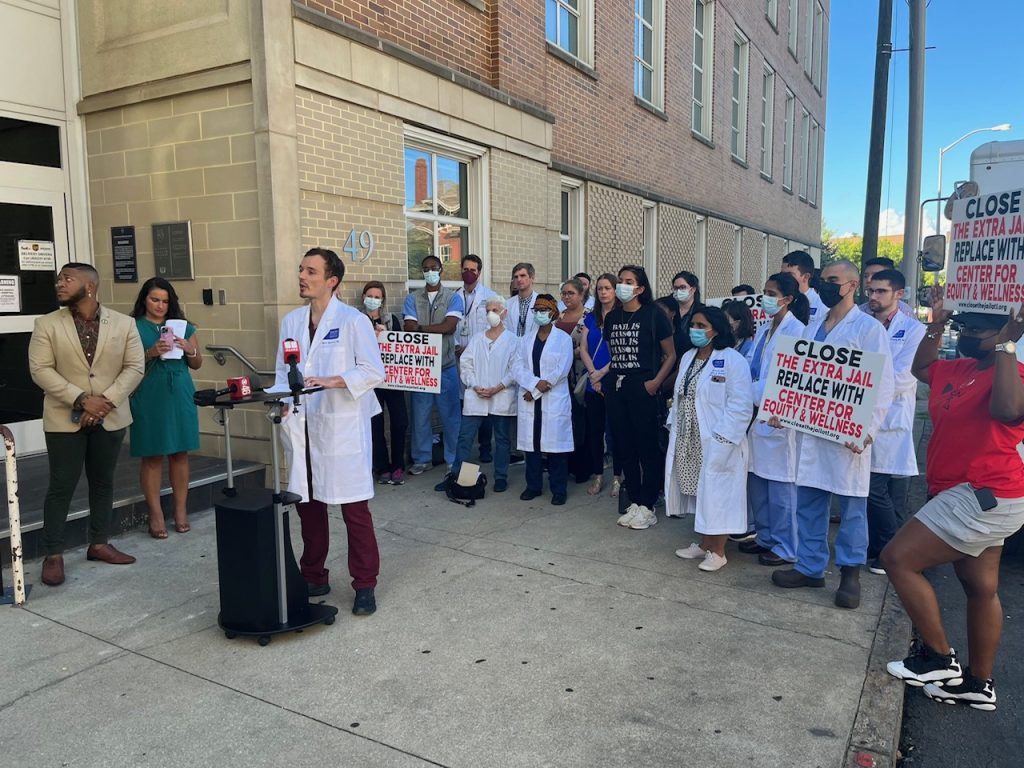

In many ways, healthcare and public health workers are uniquely positioned to make explicit the link between policing and negative health outcomes as well as popularize evidence-based, non-carceral, public safety policies.

Cop Cities, where police practice protest repression and military-style raids in mock buildings, are increasingly being built around the country. With each proposal, the urgency to more critically examine the function of policing is reaffirmed. Without a shared structural critique of policing itself, the movements against Cop Cities will remain loose coalitions of diverging interests.

For many in Atlanta, the primary concern was environmental, with the sprawling 85 acre site located in the South River Forest, one of the “lungs” of Atlanta. While certainly a just cause, the uncomfortable fact remains that a plurality, if not majority, of those who have opposed Atlanta’s Cop City were amenable to its construction in a different location. Most people still view the police as an indispensable, albeit imperfect, public service.

Without centering carceral harms in organizing efforts, many efforts opposing Cop Cities are bound to fall short. It is difficult to coherently oppose Cop Cities without critiquing police power and expansion. As such, a Cop City is a long-term investment in police maintaining their central place in local governance. For this reason, the most consequential impact may come from the ideological commitment to policing these projects represent.

If healthcare workers are serious about organizing for the betterment of all, then we must build a collective understanding of how carceral institutions worsen the very disparities we hope to eradicate.

The Consequences Of Policing

Police evangelists overstate policing’s marginal impact on crime while ignoring a myriad of adverse consequences. The direct harms cannot be overstated, including the murder of civilians at a rate unparalleled by peer nations. These deaths have become a tolerable side effect to the perceived necessity of policing. Despite the historic uprisings of 2020 calling for change, the number of police killings continues to trend upward. There are additionally tens of thousands more maimed and injured each year.

While claiming to be in the public safety business, the primary tool of policing remains criminalization. The vast majority of those arrested are for actions unrelated to safety as most would define it, with over 80% for misdemeanors. Each arrest carries with it a cascade of harms. Even when no arrest takes place, much harm can still occur.

Through constant surveillance and harassment, police seem omnipresent in communities where resources are scarce. The psychological impacts are profound and disproportionately suffered by Black people, who are more likely to be stopped, searched, and arrested. This selective use of criminalization exacerbates inequality while rarely preventing the types of crimes that impact people most. As the gateway to incarceration, policings harms are multiplied for the millions of people in America’s disastrous jails and prisons.

Who Is A Cop City For?

With such high human costs, who then are Cop Cities for? A Cop City is presented as a solution to the public’s legitimate safety concerns, with many primed to accept this narrative. This rhetorical sleight of hand allows for the laundering of a harmful project as anything but. Far from a public service, a more honest interpretation is as an investment in police morale.

Cop Cities are for recruitment and retention, they are for the police themselves. For the remaining skeptics, they are also framed as opportunities for reform. To many, this is both necessary and desirable. However, decades of procedural reforms, new technology, and ever increasing financial commitments have taken us to today’s bleak reality. Rhetoric of reform distracts from the structural changes that are required to truly enable safety and security for all. Structural change and substantive justice require a redistribution of power and resources, things police are wholly uninterested in.

Ultimately, there is little said about how the public might benefit from a Cop City, other than the implicit assumption that what is good for police is good for all. As police continue to cannibalize local budgets, and Cop Cities rise as hospitals close, this remains decidedly untrue. In a country that sees some of the worst healthcare, public health, and safety outcomes among wealthy nations, these opportunity costs cannot be ignored. Nor should the willing, at times giddy, expenditure of political capital by elected officials on Cop Cities be ignored.

The commitment of politicians to the police before the public can be explained by the relative benefits they reap in the existing power structure between themselves, wealthy corporations, and the police. This defining triad of the prison industrial complex values stability above all else, no matter the cost. Amidst intersecting crises of housing, healthcare, climate, and inequality, we can understand the spread of Cop Cities to be its own epidemic of sorts, a public health crisis of political neglect.

Policing Crime While Ignoring Harm

In public health, it is well understood that prevention is far superior to intervening only after the fact. Ostensibly, the rhetoric around policing speaks to this goal, but in practice, it is primarily a reactive institution. Much of what might be called preventative policing simply systematizes racial profiling and degrading practices such as stop and frisk. Most police time is not even spent on the crimes the public is most concerned about. For instance, a plurality of police time is spent criminalizing personal drug use, with more arrests for simple drug possession than any other crime. Violent crime, however, sees less than 5% of their time. Nationally, less than half of violent crime is reported to the police, of which they consistently solve less than half of murders.

When it comes to sexual violence, a tiny percentage is punished through the legal system. Property crime is both reported and solved at similarly low rates. It is clear policing does not deliver on its promise of safety, a truth Cop Cities will not change. Instead, at a huge opportunity cost, carceral structures create many of the conditions for crime to flourish. Policing can be understood to constantly fail upwards, incapable of addressing crime while selling the public on the myth that they simply require more resources to accomplish the job. The mirage of safety remains always on the horizon.

Worse still, the insidious use of crime as a unit of analysis for safety leaves many harms ignored. With safety viewed as solely a product of policing’s effectiveness at crime reduction, root causes and social conditions are left uninterrogated and untransformed. There is nothing to be said of the harms of environmental degradation, labor exploitation, inaccessible housing and healthcare, economic insecurity, or segregated schools. For instance, there are roughly 20,000 murders in the United States each year, all of which the police failed to prevent and many of which they struggle to “solve.” This pales in comparison to the 68,000 deaths due to a lack of adequate health insurance, over 100,000 from air pollution, and 183,000 from poverty in America each year.

If we instead define safety as the opportunity for everyone to live well and free from preventable harm, it is clear that upending policy frameworks that abandon so many is the best safety investment there is. On the other hand, investments in police are investments in the status quo. For most, this is not a status quo worth maintaining.

A World Without Cop Cities

With a stalled referendum and quickly approaching Mayoral election, Atlanta’s fight with Cop City goes on. Meanwhile, many others are building resistance to Cop Cities in their own backyard. A clear analysis of the purpose, harms, and opportunity costs of policing is imperative. Policing is an intervention with marginal benefit, significant harm, and tremendous financial cost. A medical intervention described as such would rarely be considered, let alone prioritized over numerous other choices.

Policing encourages simplistic and individualist narratives where actions are devoid of context. This absolves policymakers from their responsibility to ensure conditions where all can thrive. This myopic view is antithetical to public health, where it is understood that the way systems are created and accessed can expand or constrain opportunities. We must call out the hypocrisy of those who claim to search for solutions to safety while maintaining the very social conditions that undermine it.

For healthcare workers, abstract discussions of the importance of structural and political determinants of health are rendered meaningless without critically examining how policing, the most powerful and well-funded local institution, impacts patients’ lives.

To be an abolitionist healthcare worker is to strive towards a world free from both interpersonal and structural violence. It is to abhor all harm such that we seek to rebuild society in a way that prevents as much as possible. To that end, it is not enough to solely reduce the footprint of carceral systems. We must be a part of envisioning and building the infrastructure, institutions, and relationships that enable opportunity, safety, and health for all.

There is much work to be done, and we can look to those who have already started for guidance. In rejecting policing and criminalization as the road to safety, we may embrace new narratives of collective care. We can look to programs that prioritize housing first, treatment over punishment, economic empowerment, and center the most marginalized. Fundamentally, we need a humane approach that serves both those at risk of experiencing and perpetrating crime. As the myth of policing as safety is dispelled, we must do all we can to build a world where the idea of a Cop City becomes unimaginable.

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn't cheap to make.