New record sheds light on unreported death in Atlanta Airport customs inspection

Why did the nation’s largest police force fail to publicly acknowledge an 80 year-old Nepalese man’s death at the world’s busiest airport?

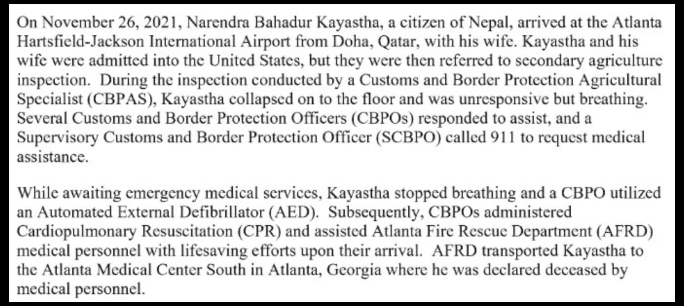

Early in the evening on Nov. 26, 2021 — Black Friday — Narendra Bahadur Kayastha and his wife walked off the flight they’d taken from Doha, Qatar, to Atlanta, Georgia. After disembarking, they followed the signs to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) screening area inside Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport.

CBP screened the couple and lawfully admitted them both into the United States. But their encounter was not finished, and they were not free to leave. A customs officer referred them to “secondary agricultural inspection” for unspecified reasons.

Kayastha, an 80-year-old citizen of Nepal who’d survived a heart attack around 30 years earlier, collapsed on the floor during secondary inspection.

He was breathing but unresponsive.

CBP officials reportedly attempted to help him. Their supervisor dialed 911. While they awaited emergency medical personnel’s arrival, Kayastha stopped breathing. An officer located an automatic external defibrillator (AED) and used it. Other officials performed CPR.

Atlanta Fire and Rescue Department (AFRD) medical personnel eventually arrived and joined in CBP officers’ efforts to save Kayastha’s life. AFRD transported him to Atlanta Medical Center – South, where he was pronounced dead.

Federal law and policy mandated the government to make a prompt, public reporting of Kayastha’s death. But CBP didn’t publicly report it.

The DetentionKills Transparency Initiative first learned of the incident nearly a year ago through federal records provided in response to a FOIA request we sent CBP back in May 2023. Our request sought the agency’s Death in Custody Reporting Act reports to DOJ over the previous 10 fiscal years. CBP didn’t give us records encompassing that period. Instead, they gave us a single year’s spreadsheet. Our appeal remains pending.

Had the agency’s FOIA office been slightly more competent in its coverup, we might never have known Narandra Kayastha’s name. (Perhaps that was the point.) But because CBP elected not to illegally redact each of the 51 names included in its spreadsheet on the bottom few pages (as it had on the top of the document), we were able to follow up with more specific records requests. We chose to dive into his unreported in-custody death because it happened in Atlanta.

Over the past year, we obtained Kayastha’s autopsy report and a host of records and other responses from local agencies saying they did not conduct investigations of his death and thus, have no records responsive to our requests.

We finally got an additional record from CBP this week: The Significant Incident Report CBP created regarding how Kayastha died. It was the story, forwarded in an email a few times, that a CBP official shared with the Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (DHS CRCL) on Nov. 27, 2021 — just over 24 hours after his death.

The Clayton County Medical Examiner’s Office requested the GBI perform an autopsy. After completing an autopsy, a pathologist concluded Kayastha died of natural causes: Organic Heart Disease.

What we don’t have, more than four years after Kayastha died, is a usable timeline from the agency that would reveal whether a delay in medical response might have contributed directly or indirectly to his death—something demonstrated in case after case of in-custody CBP deaths. I wonder if that’s something we’ll ever get. I asked for it from the DHS Office of Inspector General, to which CBP said it reported the incident shortly after Kayastha died. The agency denied expedited processing and told me to get in the backlogged waiting line.

So, that leaves CBP’s Office of Professional Responsibility. Will the agency that failed to acknowledge this in-custody death release the investigation it conducted (if any) after it occurred? Will that investigation confirm the facts in the records we received? Will we know the answers to these questions before the fourth anniversary of Kayastha’s death in custody at Hartsfield?

I don’t know. But I’ve got my suspicions.

There is a story behind each death in government custody just waiting to be told. These are stories we could all learn from, stories that could prevent future harm. But only if we tell them. Maybe there’s something worthwhile in honoring the dead by protecting the living — particularly if we believe the line between death and life is a material one that might not reflect the true nature of our consciousness and our collective spirit.

Fifty-one deaths in custody during FY21 was about as good as CBP will ever do for the next several years. It’s going to be much, much higher now that the “gloves are off.” And the reporting will be much, much harder to stick with.

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn't cheap to make.