Cornelius Taylor’s death highlights City’s pattern of violence and neglect of people experiencing homelessness

Destroyed tents and debris laid strewn on what’s known as “the backstreet” of Old Wheat Street. Don Turner, a resident of the encampment community, said no one will touch the wreckage because “blood is everywhere on the tent. That’s why we won’t let them take the tent.” On Jan. 16, 2025, Cornelius Taylor, an unhoused Atlantan, was inside his tent when a city bulldozer sweeping the encampment ran over his body more than once, killing him.

Taylor lived in the Sweet Auburn Corridor of Atlanta, across from Ebenezer Baptist Church and the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park. The attempted sweep happened prior to MLK Day weekend events. On Jan. 17, the night following Taylor’s death, a vigil was held at the site. Candles and flowers were placed on the asphalt. The city’s machinery sat at a distance, silent. Mayor Andre Dickens had yet to officially respond.

Monica Johnson, organizing director for Housing Justice League, helped to organize the vigil. “Instead of actually standing up for the legacy of Martin Luther King, the city decided to try to sweep the problems that the city faces under the rug,” Johnson said. “And they used a bulldozer and swept someone’s life away.” Advocates and neighbors spoke at the vigil, memorializing Taylor and calling for policy change.

Atlanta’s history of criminalizing homelessness

Since 2023, there has been a 7% increase in homelessness overall in Atlanta and a 41% increase in unsheltered homelessness, according to the 2024 report by Partners For HOME. These numbers are in spite of funding increases from the mayor’s office to address the issue. Councilmember Liliana Bakhtiari attended Taylor’s vigil and said funds must be better allocated to build relationships with caseworkers, and she’s proposed a moratorium on encampment sweeps in the city council. The moratorium is backed by Mayor Andre Dickens. The creation of a “homelessness task force” has also been proposed and backed by the mayor. “You should not be punished for having nothing,” Bakhtiari said.

One in eight people booked into the Atlanta City Detention Center during 2022 were people experiencing homelessness, according to a 2024 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Legislation like Senate Bill 62, passed by the Georgia legislature in spring 2023, legalized encampment sweeps and authorized police to threaten people with jail time.

Gregory Flannigan, who regularly sleeps against an abandoned building, said he is familiar with police harassment. “I’m not aware of any laws that I’m breaking, but I’m in a desperate situation,” he said.

Flannigan said police have forced him to move in the cold and rain even though he is disabled and uses a walker and that he never knows when a cop will enforce a sweep. “I have no other choice, you know, because he has the law and a gun on his side.”

Longtime Atlanta activist and Pastor James Davenport said criminalization of people experiencing homelessness is “nothing new.” He remembers seeing police officers in 2024 camped out for 24 hours under Bell Street Bridge, adjacent to Auburn Avenue, to prevent people from camping. He called these sweeps “morally wrong.”

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn’t cheap to make.

Davenport regularly gives public comment at City Hall and has spoken out against the policing of unhoused encampments. He credits the 2017 closure of Peachtree-Pine Shelter, at one time the largest shelter in the Southeast, with the increase in unhoused people on the street. He claimed Peachtree-Pine was closed in the interest of businesses downtown at the expense of people’s wellbeing. “What did they expect?” Davenport asked of the Atlanta City Council.

In November 2024, Mayor Dickens, as chair of the Invest Atlanta Board, approved $75 million in funds to build and preserve affordable housing units in the city. Willie Johnson, another one of Taylor’s friends and neighbors, told the Atlanta Community Press Collective (ACPC) that nobody should be homeless. “The government just gave them so many millions of dollars to help the homeless in the State of Georgia,” Johnson said. “Get these people out of here. You’ve got the resources and the places to do it.”

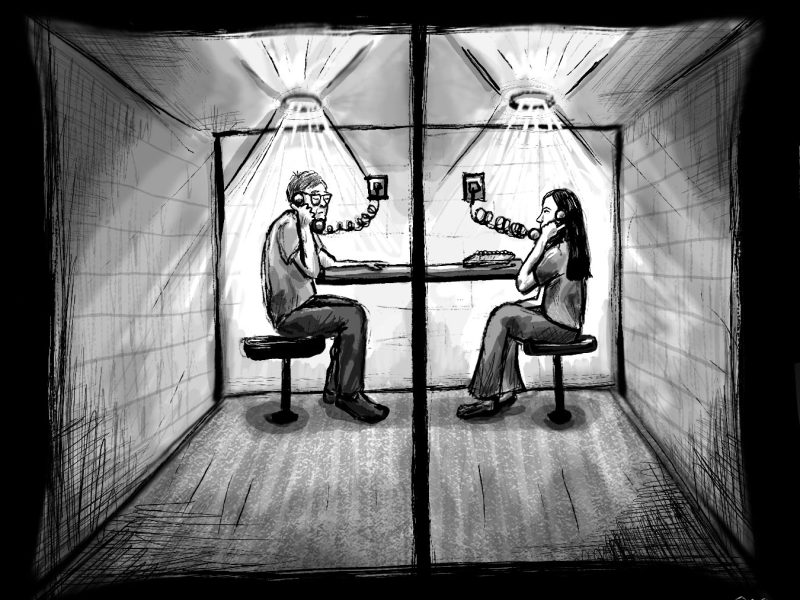

In a video released on Mayor Dickens’ social media addressing Taylor’s death more than a week later, he stated, “homelessness is not a crime.” On Jan. 23, 2024, community members, including Taylor’s mother, attempted to hand deliver a letter to Mayor Dickens at Atlanta City Hall but were barred from entry to his office.

Mutual aid efforts

Turner said that the primary need for his community is to get off of the street. He criticized charitable groups who visit the backstreet but do not engage with the people who live there.

In an effort to support people’s tangible needs, an autonomous group of organizers set up a warming center four nights after Taylor’s death at the site of his vigil. They lined a pop-up tent with mylar sheets and heated it with propane generators. Based on residents’ requests, supplies like tents, clothes, food, and even a cellphone were provided. The organizers talked to residents to build ongoing relationships to sustain their presence on the backstreet.

Latisha Morris said she has lived in Atlanta since 2000 and was Taylor’s neighbor for five years. “We’ve never had nobody bring generators,” she said. “That’s a whole new world.”

The organizers, who prefer to remain anonymous, said they were inspired to create their own community response after witnessing the city’s failure to do so and by the work of abolitionist collective Sol Underground, which runs a warming shelter with no barrier to entry.

“We just felt like this was really important to do, especially today while the nonprofits and other liberal establishment … continue the status quo and bastardize MLK’s legacy,” one organizer shared with ACPC. “There’s been national media attention about this, but it seems like there’s been not a lot of response other than prayers from the city.”

Taylor’s killing undercuts MLK’s legacy

Organizers made a banner that read, “No Murder for MLK Parade. RIP Cornelius” and hung it outside the encampment.

The banner was hung in front of Atlanta City Hall on Jan. 23 during a press conference where advocacy groups and concerned citizens, including Taylor’s family, assembled to raise awareness about Taylor’s death.

Sylvia Broome, the Outreach Program Lead for Remerge, was in attendance. Broome’s office is on Auburn Avenue, and she frequents the backstreet where Taylor died.

Broome pulled a cart full of hand warmers and socks through the row of tents and greeted people left and right through the neighborhood. One man shouted Taylor’s name, and Broome called back, “Say his name!”

“We cannot let Cornelius’s life and death go unanswered,” Broome said. “He was a leader on the street. Everybody knew him.” Taylor was known as “Psycho” by his many friends. Broome held a woman named Ms. Pat as she cried for Psycho’s memory.

Broome said that she has observed shock, anger, and grief on the street. Encampment residents have told her they feel “like nothing is going to change because nothing ever happened.” On the side of an apartment complex on Auburn Ave. was written “City of ATL Murder.” In the short time she spent on the backstreet in one afternoon, the words were painted over. To resist the silencing, she said, “Just keep saying his name, saying his name.”

Turner compared Taylor’s killing to the two Memphis Sanitation Workers who were crushed to death in 1968 by a garbage truck, inspiring a strike championed by MLK. Shortly after the sanitation workers’ strike, MLK was assassinated. Turner said Taylor’s story “is bigger.” The vigil altar remained more than a week after Taylor was killed. On the backstreet, in fading but legible handwriting, read the words “Long Live Psycho.”