DeKalb residents charged thousands in water bills, suffering for Watershed Department’s financial woes

Kay Park walked the perimeter of the Treasure Village Shopping Center on Buford Highway that she co-manages to point out water meters with the tip of her umbrella. One meter was installed without her knowledge. It was cut off, but the usage charge remains. Another meter, attached to a small ice cream shop without a public restroom, allegedly produced an $800 bill. That’s the bimonthly average water and sewer bill for a family of 8 in DeKalb. The fast food restaurant next door to the shop has no meter, just a hole in the ground.

Park immigrated from South Korea and raised her children in the United States. Since 1990, she has co-managed the shopping center property located in DeKalb County. In July 2024, she got a call from the county Department of Watershed Management (DWM) saying her account balance due was $250,000. She chose to enter a payment plan with DWM. It was either that, she said, or “We’re going to be disconnected.”

Park continues to pay $10,000 a month, for fear of a water shutoff at her tenants’ businesses.

Park’s story with DWM is not unique. Many residents face sudden, exorbitant water bills like Santina Dicaro, a lifelong resident of DeKalb County.

“They basically forced a lot of people into payment plans,” Dicaro told the Atlanta Community Press Collective (ACPC). Dicaro’s account has been in dispute since 2016. That year, DWM imposed a water service disconnection moratorium. The stated aim was to improve DWM by replacing water meters and addressing complaints without the threat of residents’ water being turned off. Residents like Dicaro didn’t receive water and sewer bills for years, and her meter was replaced.

Then, she got a text message from DWM in 2021, when the moratorium was lifted.

The text message said that she owed $8,000, Dicaro told ACPC. She called DWM, and as an explanation for the amassed charges, was told she opted for paperless billing. “I said, no, I didn’t go to paperless billing. You guys haven’t sent out a bill in years.” Dicaro said she didn’t receive any email communication from DWM during the five-year moratorium, as her bimonthly bills jumped from less than $100 to as much as $800.

A contractor confirmed that Dicaro’s meter was working and she didn’t have any water leaks, she said, but her elderly neighbor’s meter was from the 1980s and not functioning. “Are you sure there’s no way you guys linked both of these houses together?” Dicaro asked. She suggested that she may have been charged for water she did not use and requested mediation for her dispute in 2021. She is still awaiting resolution.

Dicaro said she is disabled, receives social security, and lives on a limited income. She says she can’t afford a 40-to-80-month payment plan that would add hundreds to her monthly bills for years.

Her account balance stands around $9,000—indicating to Dicaro that in the past three years after her neighbor’s meter was fixed, she herself used only $1,000 worth of water. The lack of resolution is “very, very stressful and very anxiety-producing,” she said, and she is never sure if her water will be on in the morning. She worries over the looming possibility that she could lose her house if the county put a lien on her property for unpaid bills.

“Zero accountability”

Dicaro suspected the bigger bills started when DWM installed new meters, and she’s not alone. DeKalb resident Elizabeth Shore started receiving bills for water usage at an empty lot in 2015, where she was building a new home. Shore said DWM installed iPerl meters on her property, a type of “smart” meter that was proven to incorrectly record water usage. She said she has yet to receive full acknowledgment or compensation for the faulty meter.

In e-mail exchanges with DWM, which Shore says have been largely ignored, she demanded to know why in one hour “I was charged for usage of 689 and 738 gallons,” and how she was charged for 33,600 gallons of water in a house that she and her family did not yet occupy. Her billing was erratic, going from impossibly high bills to “about a year without any water bills at all,” Shore claimed.

Shore’s disputed account balance due is around $10,000. DWM demanded she pay, in her words, “any amount” to avoid triggering a “disconnect order” and a water shutoff. She now pays the monthly water bills but is awaiting mediation. She attempted to enter a mediation process with DWM in December 2023, but a year later, the process still has not been initiated. Shore emailed DWM asking for assistance with her many invoices and has not received a response.

“I think this is the most disorganized, unaccountable department in our state,” Shore said, citing DWM’s “zero accountability.” She is critical of the proposed annual 6-10% water rate increase for residents over ten years.

“I can’t imagine,” Shore said, “raising the rates when they can’t even run this department in an organized fashion in the past decade.”

“We are all affected”

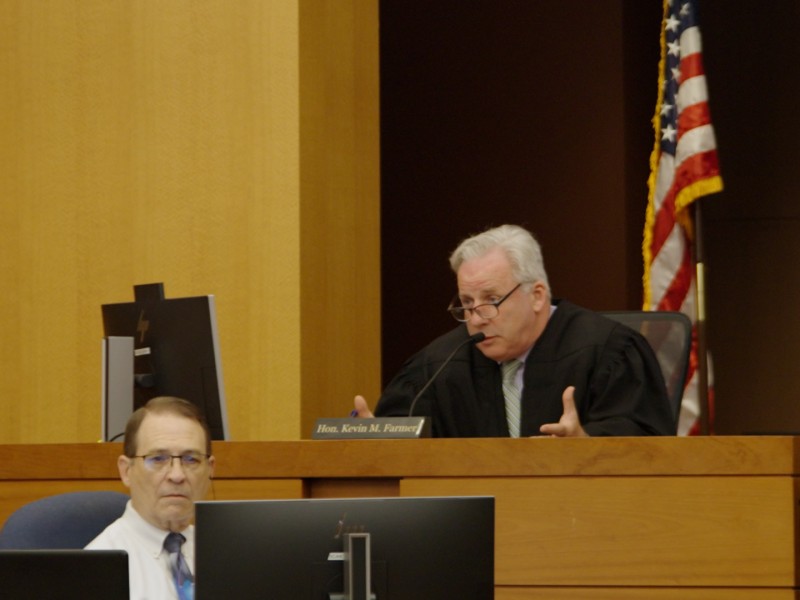

On Dec. 10, The DeKalb County Board of Commissioners (BOC) deferred the vote on a water rate increase to January 2025. Commissioner Michelle Long Spears outlined resolutions to protect residents at the Dec. 13 Public Works and Infrastructure (PWI) Committee meeting. These resolutions were drafted with the DeKalb Water Watch (DWW) Coalition, where Katherine Maddox works as a community advocate.

“There’s been a lot of broken trust between the county and residents over this issue,” Maddox said. In order to reestablish trust, DWW proposes shutoff protections for lower-income people, people with disabilities, seniors, households with children, and people whose accounts are in dispute until they can be served by the proposed Office of Water-Customer Advocacy, which would open in January 2026.

Commissioner Ted Terry led a virtual town hall Dec. 10 alongside DWM officials. During resident feedback, Brenda Pace spoke up. “We all need to know where the money is going,” she said. “I don’t trust it, and neither does anybody else.”

Pace has lived in South DeKalb for 50 years. She helped found the East Lake Terrace Neighborhood Association. Zip codes in her neighborhood are more than 20% below the federal poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. She is opposed to the water rate hikes. She plans to start a watchdog group full of diverse DeKalb residents and calls for an independent forensic financial audit of DWM.

DWM’s billing disproportionately impacts residents in “non-priority areas” like Pace’s. Despite race and class disparity, Pace said, “we all are affected.” Dicaro, who lives in Belvedere Park, a rapidly gentrifying part of Decatur, agreed, “It’s not just the lower-income neighborhoods.” The water rate increase could come out to 115% over the course of ten years. Park said this is typical of DWM, to “squeeze citizens” for “easy money to fill up their budget.”

During the public comment at a Dec. 17 BOC meeting, Maddox spoke on behalf of residents who contacted DWW. After years, their mediation processes were being scheduled with little warning. Maddox urged the BOC to pause mediations until the vote for the independent advocacy office, designed to create “a fair process for residents” and protect from water shutoffs. “Let us not rush through something so crucial,” Maddox said. “We have come so far.”

The January 2025 vote follows years of DeKalb County residents sharing their experiences in the community, online and in person. Dicaro remembers the relief of first telling her story at a DWW meeting and learning that she was not alone. “That’s how you change things.” Dicaro said. “Large groups of people getting together and making their voices heard.”

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn't cheap to make.