Black residents bear the weight of the water affordability crisis in DeKalb County

DeKalb County is facing what advocates call an egregious case of environmental racism that has been harming the Black people living there, among other vulnerable groups, and will continue to do so. On Tuesday, the DeKalb County Board of Commissioners is making a vote that could amplify the existing imbalance by adding another layer of financial pressure, placing low-income residents on an even tighter budget.

As the percentage of the Black population increases, so do water shut-offs, according to a new study by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF). In addition to the impacts on the Black community, the study found residents with disabilities and those living in three-bedroom homes, which LDF assumes to be families with children, are also disproportionately impacted.

The vulnerable groups aren’t mutually exclusive; Black families, elderly people who are disabled and people who are low-income certainly exist and overlap, compounding the chance they will face a water shut-off at some point in time.

“There’s been plenty of data that suggests that a child’s access to clean, safe, affordable water is key in their childhood [and brain] development,” David Wheaton, Atlanta native and assistant policy counsel at LDF, said. “So we don’t want to see anybody have their water shut off who has a kid in the home.”

DeKalb water inequality presents itself in other ways.

The County is under a long-standing consent decree to repair water and sewer pipes, which designated “priority” areas, mostly on the north side of the county, that they are required to fix, and “non-priority” areas, mostly on the south side.

The priority areas are predominantly white, while the non-priority areas are home to the largest concentration of Black residents in Georgia, according to DeKalb Water Watch. Dr. Jacqueline Echols, Board President of the South River Watershed Alliance, has been a cornerstone in the movement to reduce DeKalb’s pollution of the South River and has advocated on the community’s behalf for years.

She says that the concept of priority versus non-priority areas is unprecedented and that this is “the first time in the history of the Clean Water Act,” that this happened. She says she’s made various calls from local to federal levels to figure out why.

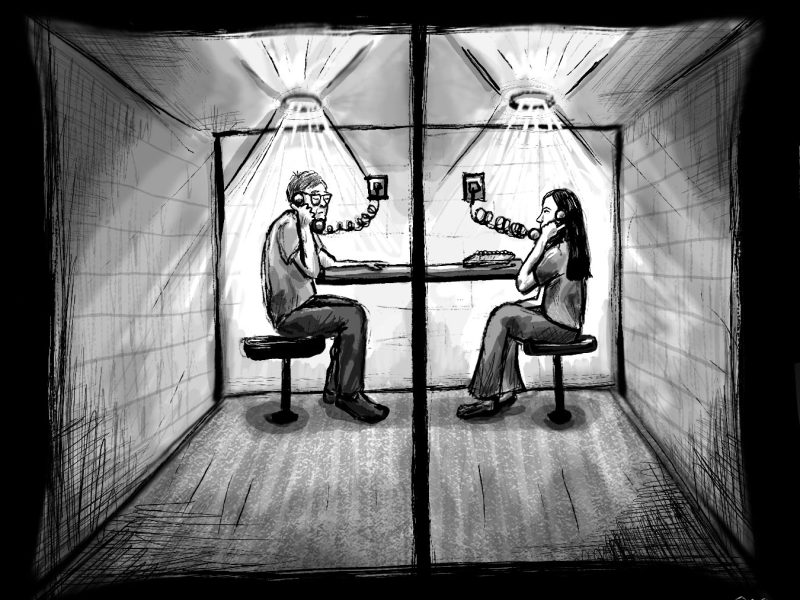

“I got no response,” she said. “So folks in south DeKalb will actually be paying for something that they won’t get.”

No paywall. No corporate sponsors. No corporate ownership.

Help keep it that way by becoming a monthly donor today.

Free news isn’t cheap to make.

Katherine Maddox from DeKalb Water Watch, a resident-led organization that works to unite community members to end DeKalb’s unjust water billing practices, said: “[Residents who are] unduly burdened by this water debt, are the ones who are systemically excluded from receiving the benefits of what they pay for.”

For low-income DeKalb residents, it could get much worse if the County’s latest proposed plan for water rate hikes moves forward.

The DeKalb Board of Commissioners (BoC) was originally considering a rate increase of 6% each year until 2027 to fund the needed system repairs. This plan was shared with residents and discussed during a Nov. 12 town hall.

The plan shifted dramatically on Dec. 3, with a new proposal for a compounding increase of 8% each year over a ten-year period. That adds up to a total increase of 115% by 2034. A $50 water bill now in 2024 would be $107.50 in 2034 if the plan goes through.

Echols’ live reaction to the increase of the rate hike was caught in an interview with Atlanta Community Press Collective. “I was reading [the update] when the phone rang hoping that [the BoC] had worked out something … it just got a lot worse,” she said, sounding despondent. “I was afraid something like this was going to happen.”

The larger rate hike was unanimously approved at the most recent BoC Public Works and Infrastructure (PWI) Committee meeting. The full BoC is expected to vote on the measure on Tuesday. But according to Echols, the plan that the PWI recommends to the BoC is usually the one they choose to go with.

How Did We Get Here?

DeKalb County needs to undertake a major infrastructure project to replace the pipes of its over 50-year-old drinking water and sewage systems.

DeKalb County is under a 2010 federal consent decree to fix its sewage system, which has been polluting neighborhood streams and the South River since the 1960s.

At the same time, officials warn that the drinking water system could face “catastrophic failure” if repairs are delayed much longer. In February, a water main break collapsed a portion of the road on McLendon Drive, which forced schools to close and instigated a boil water advisory. In April, another break left 40 homes near Dunwoody Road without water for nearly two days.

Repairs to the aging infrastructure will be costly. Commissioner Michelle Long Spears says it’s projected to cost $3 billion.

“Unfortunately, because of how the federal government and even how the state government fund localities, they have to raise a lot of that revenue and that means they have to increase rates,” Wheaton said.

“DeKalb needs infrastructure improvements, we definitely understand that,” Wheaton said. “We just don’t want that revenue to be raised on the backs of poor people and Black people.”

Echols, an environmentalist, wants the South River’s pollution cleaned up as fast as possible. But even then, she’s aware that a lot of time and money is needed to fix the problem. She believes the County is pushing too hard in too short of a timeframe and should have instead increased costs incrementally over the years to ease into it.

Nothing New: The Water Crisis

LDF has studied and reported how the water crisis has severely impacted Black communities in the U.S. for years.

“Water is essential for life, it is not like any other utility. We can go without heat, we can go without power, theoretically — water is just that one bill that you get that you cannot go without,” Wheaton said.

“If something were to go awry and they couldn’t pay their bill for one or two months,” Wheaton said. “That does not mean that somebody in that house should not be able to bathe themselves, should not be able to brush their teeth, should not be able to make a hot meal, should not be able to survive, because we all survive off of water.”

“When the infrastructure, and especially water infrastructure, tends to fail in this country, it usually has a detrimental impact to Black communities,” Wheaton said.

This is far from the first time that LDF has seen water crises harming Black communities, it’s happened in Lowndes County Alabama, Jackson Mississippi and Flint Michigan just to name a few.

In Alabama water and sewer systems have similarly excluded Black residents.

“We still have color-only treatment of how our environmental issues are dealt with, we still have separate and unequal treatment, and we are also paying the bill for our oppressors,” Alabama resident Sherrette Spicer said.

“Then let’s add this to it: so you could be black and be poor and then you’re really messed up,” Spicer said. “Our bills went up, so ugly, so nasty.”

In DeKalb, the penalty for non-payment on a bill is a water shut-off, which occurs more frequently in Black populations, according to LDF.

In 2016 DeKalb residents began reporting outrageously high and seemingly inaccurate water bills — from $1,145 to $19,000 to $82,000. In response, residents founded Dekalb Water Watch and a Facebook group called “Unbelievable Dekalb Water Bills” that now has 5,700 members.

Later that year, DeKalb County enacted a moratorium on shut-offs. In 2021 that moratorium was lifted.

In 2023, water shutoffs totaled 4,600, according to Maddox, and the county placed water bill-related liens on more than 20 residences — a process that can result in the loss of someone’s home.

Last year, residents started a petition targeting the water debt crisis with more than 1,200 signatures.

“They told me they were going to cut off my water. I’m an old woman, by myself, and you’re going to cut my water? I am afraid to take a bath,” the petition reads, attributed to 95-year-old Aielee Peebles.

Even though residents have been raising these concerns for almost a decade now, they still face many of the same problems from then, now in 2024.

Cymeve Garrett, a Black single mother and Section 8 voucher holder, received a water bill surpassing $80,000. She was then offered the “deal” of paying the County $10,000, in installments of $500 per month.

“A $10,000 bill for water for anyone is crazy,” Maddox said. “Unless she was secretly operating, without my knowledge, 50 Olympic-sized swimming pools underground on that property, she doesn’t owe that money.”

Are you a resident who wants to see the vote in action?

The DeKalb Board of Commissioners meets at 9:00 a.m. Tuesday, December 10. Public commenters must sign up to speak by 8:30 a.m.

Watch the meeting live and in person at 178 Sams Street (Multipurpose Room A1201) Decatur, GA 30030. A video recording of the meeting should be available afterward here.